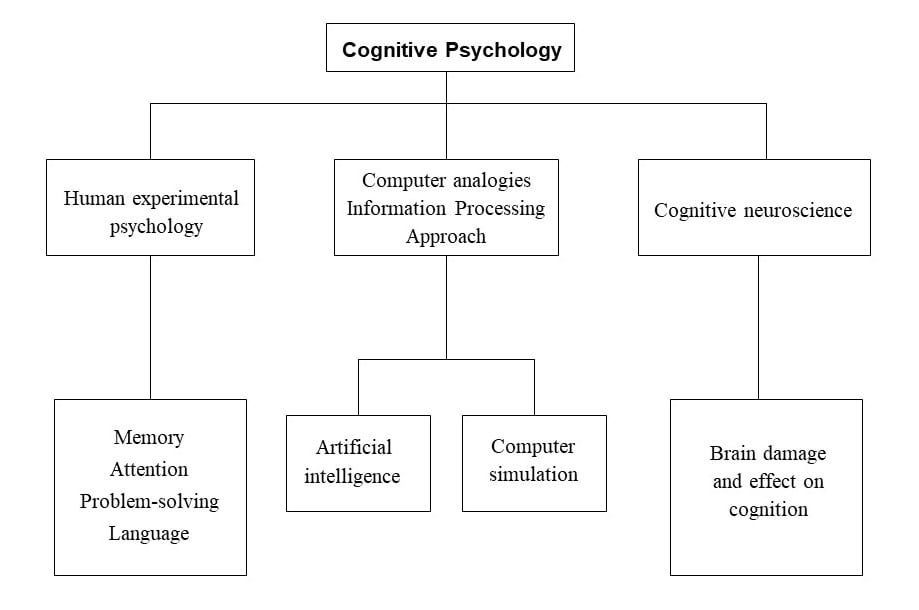

Cognitive psychology is the scientific study of the mind as an information processor. It concerns how we take in information from the outside world, and how we make sense of that information.

Cognitive psychology focuses on studying mental processes, including how people perceive, think, remember, learn, solve problems, and make decisions.

Cognitive psychologists try to build up cognitive models of the information processing that goes on inside people’s minds, including perception, attention, language, memory, thinking, and consciousness.

Cognitive psychology became of great importance in the mid-1950s. Several factors were important in this:

- Dissatisfaction with the behaviorist approach in its simple emphasis on external behavior rather than internal processes.

- The development of better experimental methods.

- Comparison between human and computer processing of information. Using computers allowed psychologists to try to understand the complexities of human cognition by comparing it with computers and artificial intelligence.

The emphasis of psychology shifted away from the study of conditioned behavior and psychoanalytical notions about the study of the mind, towards the understanding of human information processing using strict and rigorous laboratory investigation.

Summary Table

| Key Features |

|---|

| • Mediation processes • Information processing approach • Reductionism (breaks behavior down) • Nomothetic (studies the group) • Schemas (re: Kohlberg & Piaget) |

| Methodology |

|---|

| • Controlled Experiments • Physical measures (e.g., neuroimaging) • Case studies (cognitive neuroscience) • Behavioral measures (e.g., reaction time, verbal protocols) |

| Assumptions |

|---|

| • Psychology should be studied scientifically. • Information received from our senses is processed by the brain, and this processing directs how we behave. • The mind/brain processes information like a computer. We take information in, and then it is subjected to mental processes. There is input, processing, and then output. • Mediational processes (e.g., thinking, memory) occur between stimulus and response. |

| Strengths |

|---|

| • Objective measurement, which can be replicated and peer-reviewed • Real-life applications (e.g., CBT) • Clear predictions that can be can be scientifically tested |

| Limitations |

|---|

| • Reductionist (e.g., ignores biology) • Experiments have low ecological validity • Behaviourism – can’t objectively study unobservable internal behavior |

Theoretical Assumptions

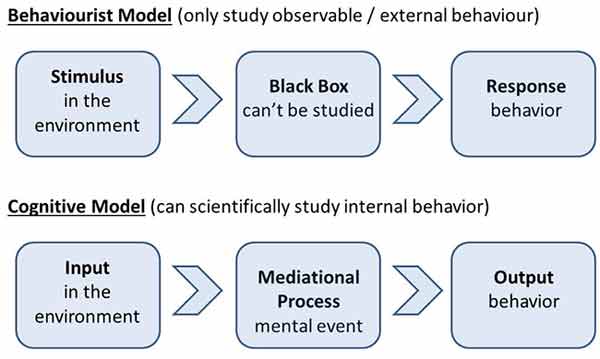

Mediational processes occur between stimulus and response:

The behaviorists approach only studies external observable (stimulus and response) behavior that can be objectively measured.

They believe that internal behavior cannot be studied because we cannot see what happens in a person’s mind (and therefore cannot objectively measure it).

However, cognitive psychologists regard it as essential to look at the mental processes of an organism and how these influence behavior.

Cognitive psychology assumes a mediational process occurs between stimulus/input and response/output.

These are mediational processes because they mediate (i.e., go-between) between the stimulus and the response. They come after the stimulus and before the response.

Instead of the simple stimulus-response links proposed by behaviorism, the mediational processes of the organism are essential to understand. Without this understanding, psychologists cannot have a complete understanding of behavior.

The mediational (i.e., mental) event could be memory, perception, attention or problem-solving, etc.

For example, the cognitive approach suggests that problem gambling is a result of maladaptive thinking and faulty cognitions. These both result in illogical errors being drawn, for example gamblers misjudge the amount of skill involved with ‘chance’ games so are likely to participate with the mindset that the odds are in their favour so they may have a good chance of winning.

Therefore, cognitive psychologists say that if you want to understand behavior, you must understand these mediational processes.

Psychology should be seen as a science:

The cognitive approach believes that internal mental behavior can be scientifically studied using controlled experiments. They use the results of their investigations as the basis for making inferences about mental processes.

Cognitive psychology uses laboratory experiments that are highly controlled so they avoid the influence of extraneous variables. This allows the researcher to establish a causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

Cognitive psychologists measure behavior that provides information about cognitive processes (e.g., verbal protocols of thinking aloud). They also measure physiological indicators of brain activity, such as neuroimages (PET and fMRI).

For example, brain imaging fMRI and PET scans map areas of the brain to cognitive function, allowing the processing of information by centers in the brain to be seen directly. Such processing causes the area of the brain involved to increase metabolism and “light up” on the scan.

These controlled experiments are replicable, and the data obtained is objective (not influenced by an individual’s judgment or opinion) and measurable. This gives psychology more credibility.

Replicability is a crucial concept of science as it ensures that people can validate research by repeating the experiment to ensure that an accurate conclusion has been reached.

Without replicability, a scientific finding may be invalid as it cannot be falsified. Additionally, scientific research relies on the peer review of research to ensure that the research is justifiable.

Without replicability, it would be impossible to justify the accuracy of the research.

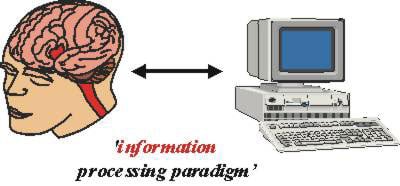

Humans are information processors:

Cognitive psychology has been influenced by developments in computer science and analogies are often made between how a computer works and how we process information.

Information processing in humans resembles that in computers, and is based on transforming information, storing and processing information, and retrieving information from memory.

Information processing models of cognitive processes such as memory and attention assume that mental processes follow a linear sequence.

For example:

-

- Input processes are concerned with the analysis of the stimuli.

-

- Storage processes cover everything that happens to stimuli internally in the brain and can include coding and manipulation of the stimuli.

-

- Output processes are responsible for preparing an appropriate response to a stimulus.

This has led to models which show information flowing through the cognitive system, such as the multi-store model of memory.

Information Processing Paradigm

The cognitive approach began to revolutionize psychology in the late 1950s and early 1960s to become the dominant approach (i.e., perspective) in psychology by the late 1970s. Interest in mental processes was gradually restored through the work of Jean Piaget and Edward Tolman.

Tolman was a ‘soft behaviorist’. His book Purposive Behavior in Animals and Man in 1932 described research that behaviorism found difficult to explain. The behaviorists’ view was that learning occurred due to associations between stimuli and responses.

However, Tolman suggested that learning was based on the relationships formed amongst stimuli. He referred to these relationships as cognitive maps.

But the arrival of the computer gave cognitive psychology the terminology and metaphor it needed to investigate the human mind.

The start of the use of computers allowed psychologists to try to understand the complexities of human cognition by comparing it with something simpler and better understood, i.e., an artificial system such as a computer.

The use of the computer as a tool for thinking about how the human mind handles information is known as the computer analogy. Essentially, a computer codes (i.e., changes) information, stores information, uses information and produces an output (retrieves info).

The idea of information processing was adopted by cognitive psychologists as a model of how human thought works.

The information processing approach is based on several assumptions, including:

- Information made available from the environment is processed by a series of processing systems (e.g., attention, perception, short-term memory);

- These processing systems transform, or alter the information in systematic ways;

- The aim of research is to specify the processes and structures that underlie cognitive performance;

- Information processing in humans resembles that in computers.

The Role of Schemas

Schemas can often affect cognitive processing (a mental framework of beliefs and expectations developed from experience). As you get older, these become more detailed and sophisticated.

A schema is a “packet of information” or cognitive framework that helps us organize and interpret information. They are based on our previous experience.

Schemas help us to interpret incoming information quickly and effectively; this prevents us from being overwhelmed by the vast amount of information we perceive in our environment.

However, it can also lead to distortion of this information as we select and interpret environmental stimuli using schemas that might not be relevant.

This could be the cause of inaccuracies in areas such as eyewitness testimony. It can also explain some errors we make when perceiving optical illusions.

History of Cognitive Psychology

- Kohler (1925) published a book called, The Mentality of Apes. In it, he reported observations which suggested that animals could show insightful behavior. He rejected behaviorism in favour of an approach which became known as Gestalt psychology.

- Norbert Wiener (1948) published Cybernetics: or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, introducing terms such as input and output.

- Tolman (1948) work on cognitive maps – training rats in mazes, showed that animals had an internal representation of behavior.

- Birth of Cognitive Psychology often dated back to George Miller’s (1956) “ The Magical Number 7 Plus or Minus 2: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information.” Milner argued that short-term memory could only hold about seven pieces of information, called chunks.

- Newell and Simon’s (1972) development of the General Problem Solver.

- In 1960, Miller founded the Center for Cognitive Studies at Harvard with the famous cognitivist developmentalist, Jerome Bruner.

- Ulric Neisser (1967) publishes “ Cognitive Psychology”, which marks the official beginning of the cognitive approach.

- Process models of memory Atkinson & Shiffrin’s (1968) Multi-Store Model.

- The cognitive approach is highly influential in all areas of psychology (e.g., biological, social, neuroscience, developmental, etc.).

Issues and Debates

Free will vs. Determinism

The position of the cognitive approach is unclear as it argues, on the one hand, the way we process information is determined by our experience (schemas).

On the other hand in, the therapy derived from the approach (CBT) argues that we can change the way we think.

Nature vs. Nurture

The cognitive approach takes an interactionist view of the debate as it argues that our behavior is influenced by learning and experience (nurture), but also by some of our brains’ innate capacities as information processors e.g., language acquisition (nature).

Holism vs. Reductionism

The cognitive approach tends to be reductionist as when studying a variable, it isolates processes such as memory from other cognitive processes.

However, in our normal life, we would use many cognitive processes simultaneously, so it lacks validity.

Idiographic vs. Nomothetic

It is a nomothetic approach as it focuses on establishing theories on information processing that apply to all people.

Critical Evaluation

B.F. Skinner criticizes the cognitive approach as he believes that only external stimulus-response behavior should be studied as this can be scientifically measured.

Therefore, mediation processes (between stimulus and response) do not exist as they cannot be seen and measured. Due to its subjective and unscientific nature, Skinner continues to find problems with cognitive research methods, namely introspection (as used by Wilhelm Wundt).

Humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers believes that the use of laboratory experiments by cognitive psychology has low ecological validity and creates an artificial environment due to the control over variables. Rogers emphasizes a more holistic approach to understanding behavior.

The cognitive approach uses a very scientific method which are controlled and replicable, so the results are reliable. However, experiments lack ecological validity because of the artificiality of the tasks and environment, so it might not reflect the way people process information in their everyday life.

For example, Baddeley (1966) used lists of words to find out the encoding used by LTM, however, these words had no meaning to the participants, so the way they used their memory in this task was probably very different than they would have done if the words had meaning for them. This is a weakness as the theories might not explain how memory works outside the laboratory.

These are used to study rare conditions which provide an insight on the working of some mental processes i.e. Clive Wearing, HM. Although case studies deal with very small sample so the results cannot be generalized to the wider population as they are influenced by individual characteristics, they allow us to study cases which could not be produced experimentally because of ethical and practical reasons.

The information processing paradigm of cognitive psychology views the minds in terms of a computer when processing information. However, although there are similarities between the human mind and the operations of a computer (inputs and outputs, storage systems, the use of a central processor), the computer analogy has been criticized by many.

The approach is reductionist as it does not consider emotions and motivation, which influence the processing of information and memory. For example, according to the Yerkes-Dodson law anxiety can influence our memory.

Such machine reductionism (simplicity) ignores the influence of human emotion and motivation on the cognitive system and how this may affect our ability to process information.

Behaviorism assumes that people are born a blank slate (tabula rasa) and are not born with cognitive functions like schemas, memory or perception.

The cognitive approach does not always recognize physical (biological psychology) and environmental (behaviorist approach) factors in determining behavior.

Cognitive psychology has influenced and integrated with many other approaches and areas of study to produce, for example, social learning theory, cognitive neuropsychology, and artificial intelligence (AI).

Another strength is that the research conducted in this area of psychology very often has applications in the real world.

For example, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been very effective in treating depression (Hollon & Beck, 1994), and moderately effective for anxiety problems (Beck, 1993). CBT’s basis is to change how the person processes their thoughts to make them more rational or positive.

By highlighting the importance of cognitive processing, the cognitive approach can explain mental disorders such as depression, where Beck argues that it is the negative schemas we hold about the self, the world, and the future which lead to depression rather than external events.

References

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Chapter: Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In Spence, K. W., & Spence, J. T. The psychology of learning and motivation (Volume 2). New York: Academic Press. pp. 89–195.

Beck, A. T, & Steer, R. A. (1993). Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. San Antonio: Harcourt Brace and Company.

Hollon, S. D., & Beck, A. T. (1994). Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies. In A. E. Bergin & S.L. Garfield (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (pp. 428—466). New York: Wiley.

Köhler, W. (1925). An aspect of Gestalt psychology. The Pedagogical Seminary and Journal of Genetic Psychology, 32(4), 691-723.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63 (2): 81–97.

Neisser, U (1967). Cognitive psychology. Appleton-Century-Crofts: New York

Newell, A., & Simon, H. (1972). Human problem solving. Prentice-Hall.

Tolman, E. C., Hall, C. S., & Bretnall, E. P. (1932). A disproof of the law of effect and a substitution of the laws of emphasis, motivation and disruption. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 15(6), 601.

Tolman E. C. (1948). Cognitive maps in rats and men. Psychological Review. 55, 189–208

Wiener, N. (1948). Cybernetics or control and communication in the animal and the machine. Paris, (Hermann & Cie) & Camb. Mass. (MIT Press).