Summary

- The law of effect states that connections leading to satisfying outcomes are strengthened while those leading to unsatisfying outcomes are weakened.

- Positive emotional responses, like rewards or praise, strengthen stimulus-response connections. Unpleasant responses weaken them.

- This establishes reinforcement as central to efficient and enduring learning. Reward is more impactful than punishment.

- Connections grow most robust when appropriate associations lead to fulfilling outcomes. The “effect” generated shapes future behavioral and cognitive patterns.

Thorndike Theory

The law of effect states that behaviors followed by pleasant or rewarding consequences are more likely to be repeated, while behaviors followed by unpleasant or punishing consequences are less likely to be repeated.

The principle was introduced in the early 20th century through experiments led by Edward Thorndike, who found that positive reinforcement strengthens associations and increases the frequency of specific behaviors.

The law of effect principle developed by Edward Thorndike suggested that:

“Responses that produce a satisfying effect in a particular situation become more likely to occur again in that situation, and responses that produce a discomforting effect become less likely to occur again in that situation (Gray, 2011, p. 108–109).”

Edward Thorndike (1898) is famous in psychology for his work on learning theory that leads to the development of operant conditioning within behaviorism.

Whereas classical conditioning depends on developing associations between events, operant conditioning involves learning from the consequences of our behavior.

Skinner wasn’t the first psychologist to study learning by consequences. Indeed, Skinner’s theory of operant conditioning is built on the ideas of Edward Thorndike.

Experimental Evidence

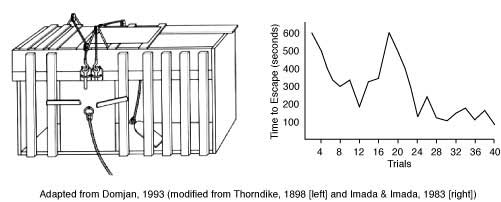

Thorndike studied learning in animals (usually cats). He devised a classic experiment using a puzzle box to empirically test the laws of learning.

- Thorndike put hungry cats in cages with automatic doors that could be opened by pressing a button inside the cage. Thorndike would time how long it took the cat to escape.

- At first, when placed in the cages, the cats displayed unsystematic trial-and-error behaviors, trying to escape. They scratched, bit, and wandered around the cages without identifiable patterns.

- Thorndike would then put food outside the cages to act as a stimulus and reward. The cats experimented with different ways to escape the puzzle box and reach the fish.

- Eventually, they would stumble upon the lever which opened the cage. When it had escaped, the cat was put in again, and once more, the time it took to escape was noted. In successive trials, the cats would learn that pressing the lever would have favorable consequences, and they would adopt this behavior, becoming increasingly quick at pressing the lever.

- After many repetitions of being placed in the cages (around 10-12 times), the cats learned to press the button inside their cages, which opened the doors, allowing them to escape the cage and reach the food.

Edward Thorndike put forward a Law of Effect, which stated that any behavior that is followed by pleasant consequences is likely to be repeated, and any behavior followed by unpleasant consequences is likely to be stopped.

Critical Evaluation

Thorndike (1905) introduced the concept of reinforcement and was the first to apply psychological principles to the area of learning.

His research led to many theories and laws of learning, such as operant conditioning. Skinner (1938), like Thorndike, put animals in boxes and observed them to see what they were able to learn.

Thorndike’s theory has implications for teaching such as preparing students mentally, using drills and repetition, providing feedback and rewards, and structuring material from simple to complex.

B.F. Skinner built upon Thorndike’s principles to develop his theory of operant conditioning. Skinner’s work involved the systematic study of how the consequences of a behavior influence its frequency in the future. He introduced the concepts of reinforcement (both positive and negative) and punishment to describe how consequences can modify behavior.

The learning theories of Thorndike and Pavlov were later synthesized by Hull (1935). Thorndike’s research drove comparative psychology for fifty years, and influenced countless psychologists over that period of time, and even still today.

Criticisms

Critiques of the theory include that it views humans too mechanistically like animals, overlooks higher reasoning, focuses too narrowly on associations, and positions the learner too passively.

Here is a summary of some of the main critiques and limitations of Thorndike’s learning theory:

- Using animals like cats and dogs in experiments is controversial when making inferences about human learning, since animal and human cognition differ.

- The theory depicts humans as mechanistic, like animals, driven by automatic trial-and-error processes. However, human learning is more complex and not entirely explained through stimulus-response connections.

- By overemphasizing associations, the theory overlooks deeper reasoning, understanding, and meaning construction involved in learning.

- Definitions and conceptual knowledge are ignored in favor of strengthening mechanistic stimulus-response bonds.

- Learners are passive receptors rather than active or creative; educators provide rigid structured curricula rather than let learners construct knowledge.

- Learners require constant external motivation and reinforcement rather than having internal drivers.

- Failures are punished, and discipline is stressed more than conceptual grasp or successful processes.

- The focus is on isolated skills, facts, and hierarchical sequencing rather than integrated understanding.

- Evaluation only measures passive responses and test performance rather than deeper learning processes or contexts.

Application of Thorndike’s Learning Theory to Students’ Learning

Thorndike’s theory, when applied to student learning, emphasizes several key factors – the role of the environment, breaking tasks into detail parts, the importance of student responses, building stimulus-response connections, utilizing prior knowledge, repetition through drills and exercises, and giving rewards/praise.

Learning is results-focused, with the measurement of observable outcomes. Errors are immediately corrected. Repetition aims to ingrain behaviors until they become habit. Rewards strengthen desired behaviors, punishment weakens undesired behaviors.

Some pitfalls in the application include teachers becoming too authoritative, one-way communication, students remaining passive, and over-reliance on rote memorization. However, his theory effectively promotes preparation, readiness, practice, feedback, praise for progress, and sequential mastery from simple to complex.

Teachers arrange hierarchical lesson materials starting from simple concepts, break down learning into parts marked by specific skill mastery, provide examples, emphasize drill/repetition activities, offer regular assessments and corrections, deliver clear brief instructions, and utilize rewards to motivate. This style is most applicable for skill acquisition requiring significant practice.

For students, the theory instills habits of repetition, progress tracking, and associate positive outcomes to effort.

It can, however, be limited if students remain passive receivers of instruction rather than active or collaborative learners. Proper application encourages student discipline while avoiding strict, punishing environments.

Additional Laws of Learning In Thorndike’s Theory

Thorndike’s theory explains that learning is the formation of connections between stimuli and responses. The laws of learning he proposed are the law of readiness, the law of exercise, and the law of effect.

-

Law of Readiness

- The law of readiness states that learners must be physically and mentally prepared for learning to occur. This includes not being hungry, sick, or having other physical distractions or discomfort.

- Mentally, learners should be inclined and motivated to acquire the new knowledge or skill. If they are uninterested or opposed to learning it, the law states they will not learn effectively.

- Learners also require certain baseline knowledge and competencies before being ready to learn advanced concepts. If those prerequisites are lacking, acquisition of new info will be difficult.

- Overall, the law emphasizes learners’ reception and orientation as key prerequisites to successful learning. The right mindset and adequate foundation enables efficient uptake of new material.

-

Law of Exercise

- The law of exercise states that connections are strengthened through repetition and practice.

- Frequent trials allow errors to be corrected and neural pathways related to the knowledge/skill to become more engrained.

- As associations are reinforced through drill and rehearsal, retrieval from long term memory also becomes more efficient.

- In sum, repeated exercise of learned material cements retention and fluency over time. Forgetting happens when such connections are not actively preserved through practice.

References

Gray, P. (2011). Psychology (6th ed.) New York: Worth Publishers.

Hull, C. L. (1935). The conflicting psychologies of learning—a way out. Psychological Review, 42(6), 491.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. New York: Appleton-Century.

Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 2(4), i-109.

Thorndike, E. L. (1905). The elements of psychology. New York: A. G. Seiler.