Key Takeaways

- Phrenology, or craniology, is a now-discredited system for analyzing a person’s strengths and weaknesses based on the size and shape of regions on the skull.

- The Viennese physiologist Franz Joseph Gall invented phrenology in the late 18th century. His student, Spurzheim, and Spurzheim’s student, Combe, would alter and popularize phrenology throughout Europe and the United States.

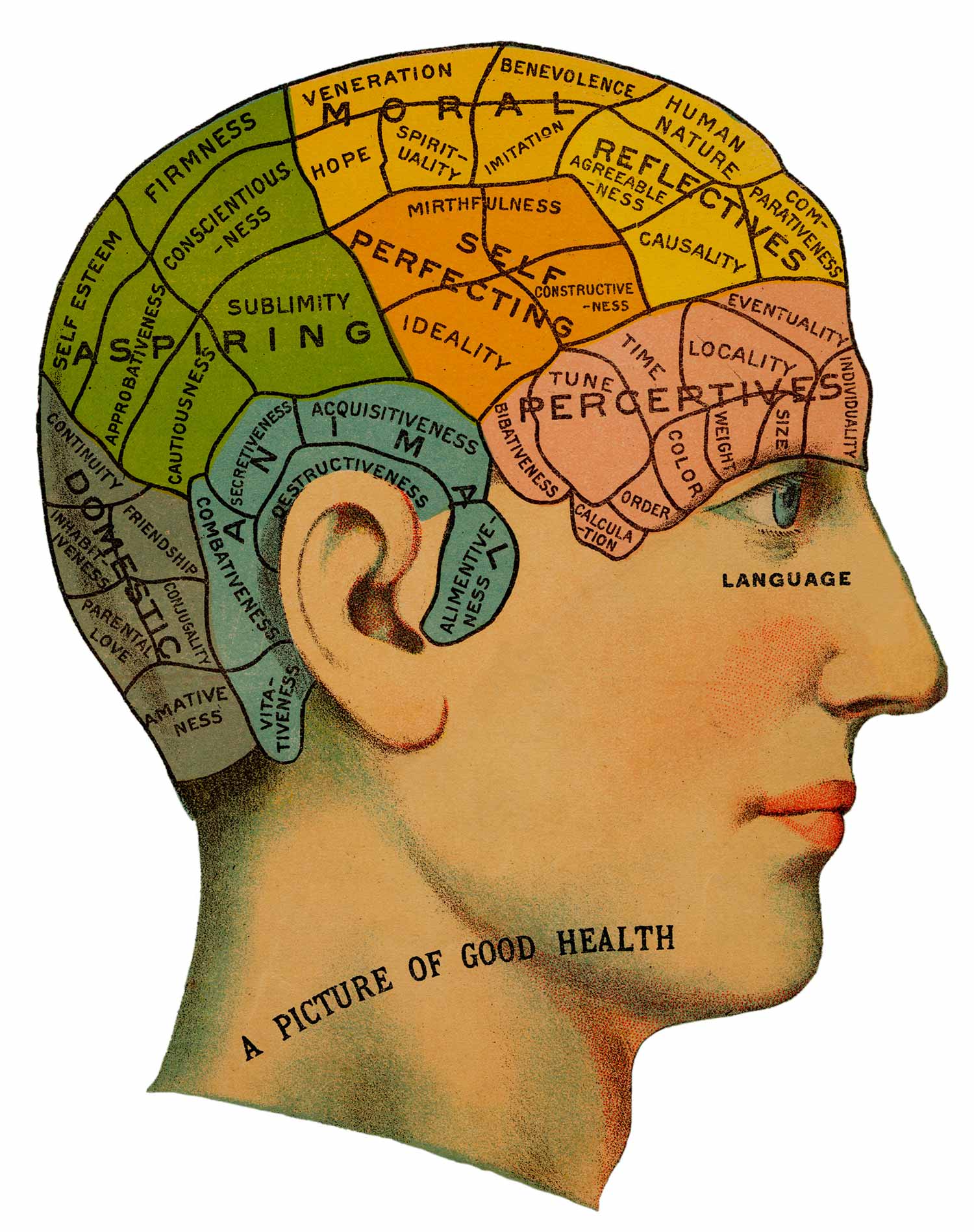

- According to phrenology, there are anywhere between 26 and 40 distinct regions, or “organs,” in the brain associated with mental facilities. The bigger the region relative to the rest of the skull, the more Gall believed it was used.

- Phrenology, even at the peak of its popularity, was controversial and garnered immense criticism for reasons ranging from the methods of Gall’s experiments to its supposed promotion of materialism and atheism. Modern MRI studies have provided a rigorous argument against phrenology.

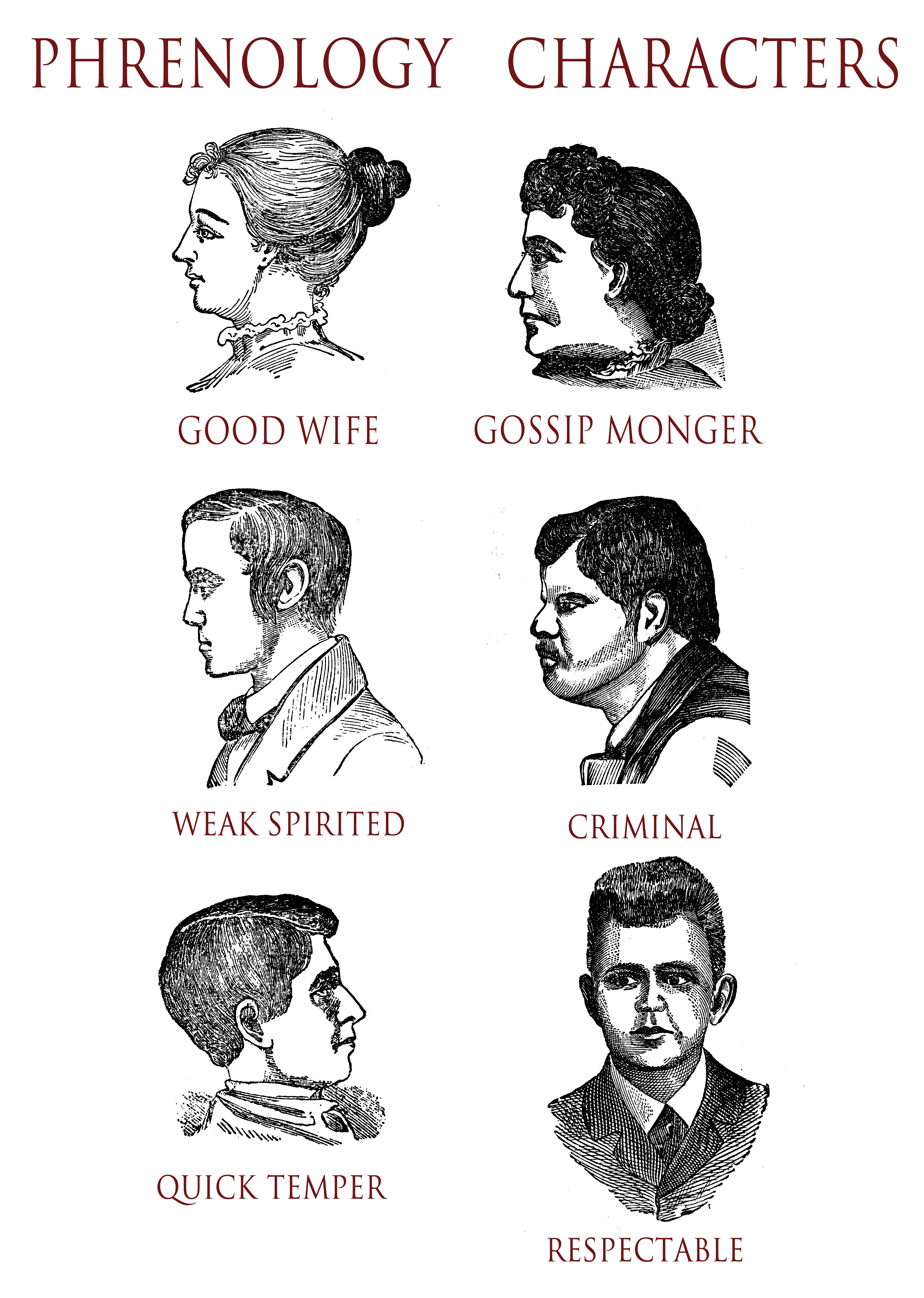

- Although Gall believed that the phrenological structure of brains was fixed, his successors contended that these traits were malleable. This provided justification for phrenology as an early biological theory of crime as well as in educating those of lower classes about their position in society by 19th-century advocates.

- Despite its defunct status, phrenology has greatly influenced the development of neuroscience, notably the idea that certain functions are controlled by certain regions of the brain and the existence of white matter.

History and Overview

The term phrenology, sometimes called craniology, refers to a now-discredited system for analyzing a person’s psychological strengths and weaknesses by attempting to correlate the size and shape of regions of the skull with the supposed functions of the underlying areas of the brain.

Phrenology was invented by Franz Joseph Gall in the late 18th century in Vienna and had a wide impact on medicine, science, and culture in the first half of the 19th century in Europe and North America.

In the 1790s, Gall formulated four fundamental themes that guided his research in phrenology:

-

Moral and intellectual qualities are innate;

-

The functioning of someone’s moral and intellectual systems depends on their organ and body structure;

-

The brain is the organ that contains all of someone’s mental facilities, tendencies, and feelings — what he called the “organ of the soul;”

-

The brain is composed of as many organs as there are faculties, tendencies, and feelings.

These four theses were controversial at the time (Greenblatt, 1995). However, the second and third of these are similar to the modern theory of brain localization.

Gall claimed that he had been observing human behaviors since childhood and that he was struck by the prominence of the eyes of his classmates, who had good memories, particularly verbal memories (Greenblatt, 1995).

From this observation, he reasoned that the shape of the skull might be determined by the configuration of the underlying brain and, thus, that particular parts of the brain are responsible for the observed behaviors.

If some particular behavior is exaggerated in many people, and the skulls of those people are consistently prominent in the same place, then the corresponding brain region must be larger than usual (Greenblatt, 1995).

Phrenology was based on the principle of cerebral localization — which postulates that different regions of the brain are associated with different cognitive processes.

Why was phrenology so popular?

To understand why phrenology became so popular in the 19th century, scholars consider it important to consider the themes in science and culture in the late 18th century.

Greenblatt (1995) argued that there were two aspects of this that led to the spread of phrenology: firstly, the state of neuroscience at the time and, secondly, the central role of Christian theology in scientific thinking.

In the late 18th century, so-called “neurophysiology” was based on the ideas of the Roman doctor Galen of Pergamon, who wrote in the 2nd century. Although these were not universally accepted, there was no theory to replace them (Greenblatt, 1995).

According to Galen, there was a “vital spirit” originating in the left ventricle of the heart. This spirit, or pneuma, was carried to the base of the brain by the carotid arteries. The role of the brain, in this theory, was to purify and filter this liquid pneuma, resulting in cerebrospinal fluid.

Galen’s theories of medicine were humoral — concerned with the liquid components of the body. He believed that solid organs were primarily processors for the humors and pneumas.

One of the 18th century’s lines of thought that preceded phrenology was the “search for the sensorium commune” (Greenblatt, 1995).

This sensorium commune was supposed to be the part of the brain that controlled all senses. This part of the brain was often correlated with the “soul” in the theological sense.

In addition to difficulties arising from the stronghold of Galen’s humoral theory over 18th-century neuromedicine, there was also active governmental and ecclesiastical interference in scientific research.

Phrenology received criticism from ecclesiasticism. Emperor Francis I prohibited Gall from publicly lecturing in Austria in 1802 on the basis that the ideas of phrenology were subversive to religion and morals (Morin, 2014).

As a result, Gall and Johann Gaspar Spurzheim, a student of Gall, moved to Paris, where Spurzheim systematized and extended Gall’s system.

Spurzheim would move to England and publish The Physiognomical System of Drs. Gall and Spurzheim (Greenblatt, 1995), which spurred the phrenological movement in England and the United States.

Explanation of Theory

Phrenologists measured the skull and used the bumps in the skull to determine the cognitive and psychological characteristics of a human. Gall believed that each faculty.

The mind was located in one of 26 distinct regions, or “organs” ” with connective white matter in between. Followers of Gall would go on to add additional regions.

Gall’s original list of 26 organs were: the instinct to reproduce; parental love; fidelity; self defense; murder; cunningness; sense of property; pride; ambition and vanity; caution; educational aptness; sense of location; memory; verbal memory; language; color perception; musical talent; arithmetic, counting, and time; mechanical skill; wisdom; metaphysical lucidity; wit, causality, and sense of inference; poetic talent; good-nature, compassion, and moral sense; mimic; and sense of God and religion (Morin, 2014).

Essentially, phrenologists believed that the larger or more prominent a region was, the more likely that person was to have a particular personality trait. Gall believed that an enlarged organ meant that a patient used that particular organ extensively.

In order to measure the relative size of the skull’s regions, phrenologists would use their knowledge of the shapes of heads and organ positions to determine the overall natural strengths and weaknesses of an individual.

Phrenologists would sometimes use head-shaped measuring devices. For example, those who exhibited large amounts of parental love would supposedly have a more prominent bump on the very back of the skull.

While someone said to be destructive would have prominence on the skull surrounding the top of their ear (Morin, 2014).

Later, Spurzheim would modify Gall’s theories by eliminating all faculties that were inherently evil, such as the faculty of murder and carnivorousness.

Additionally, he added six further facilities and changed many of the descriptions of the remaining organs. Spurzheim also categorized the organs into larger categories, which were based on propensities, sentiments, and intellect.

Believing that an individual’s faculties could be modified over the course of a lifetime, Spurzheim modified the strict deterministic view of people and introduced the potential for treatment and change. These traits, however, were still heritable (Morin, 2014).

Applications

Phrenology in 19th century Britain

Phrenological societies began to appear in London and other cities by the 1820s and were discussed in many medical societies (Greenblatt, 1995).

Greenblatt argues that phrenology was popular in Britain in the 1820s and 1830s because it seemed to offer a practical approach to a major social problem.

At the time, the adverse effects of the Industrial Revolution were becoming very obvious, resulting in major inequality between the rich and the poor.

Although there were never any violent urban upheavals of major proportions in Britain, many in the middle and upper classes feared this possibility.

As a result of this perceived threat, leaders and activists set up mechanisms to teach lower classes about their proper, subservient roles and society and to help them improve themself.

The establishment of these “mechanics institutes,” which were organized to provide practical and moral instruction for skilled workers and artisans, incorporated phrenology until the 1830s.

Phrenology in Criminology

Phrenology was one of the earliest biological theories of crime and laid the foundation for the development of the biological school of criminology (Morin, 2014).

After Gall, phrenologists viewed the brain as malleable and capable of change. This view allowed phrenologists to believe that criminals were not responsible for their crimes and that it was possible for people to be cured of their criminology (Morin, 2014).

Combe, a student of Spurzheim, developed a way to type three classes of people according to their criminal responsibility. The first of these classes consisted of those who had large moral and intellectual organs, with organs of lower propensities being more moderate in size.

These people, according to Combe, had free will and ought to be punished for their criminal acts. The second class of people had organs that were all large but equal in their largeness.

While these people possessed strong criminal impulses, they were still responsible for their criminal acts. Finally, the third class of people consisted of people who possessed large organs of lower propensities and small moral and intellectual organs.

These people, according to Combe, were pathologically habitual criminals, moral patients in need of restraint, but not punishment (Lucie, 2007; Morin, 2014).

Ultimately, criminal phrenology would serve as the foundation for the development of the positivist biological school of criminology.

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution would come to further influence phrenologists — and particularly the theory of atavism, according to which criminals are physiological throwbacks to earlier stages of human evolution (Lombroso, 2005; Morin, 2014).

Discrediting

Even at the height of its popularity in the early 1800s, phrenology was controversial and is now considered discredited by modern science. By the 1840s, pseudoscience was mostly discredited as a scientific theory.

In its time, phrenology received criticism for numerous reasons. Phrenologists had not been able to identify how many mental organs there were and had difficulty locating where they were.

Contemporary experiments on pigeons showed that the loss of parts of the brain either caused no loss of function or the loss of a completely different function than what would have been predicted by phrenology (Flourens, 1846).

Young (1968) provided a critique of Gall’s original data. He argued that Gall was often unable to obtain direct evidence about the size of the organs in the brain since he mostly made his observations on living organisms.

Young believed that Gall was “extremely predisposed” to see a coronal prominence or large cerebral organ when he already had evidence of behavior.

In essence, Young argued that Gall’s methodology was circular, with each new case strengthening his belief that he had found a valid correlation (Young, 1968; Greenblatt, 1995).

Phrenology was also criticized from its inception by those who believed it promoted materialism — the belief that all phenomena are caused by material processes — and atheism, and thus the destruction of morality (Greenblatt, 1995).

Nonetheless, phrenologists still exist today. Several scientists have used MRI studies as a way of refuting the practice using modern scientific methods. Parker Jones, Alfaro-Almagro, and Jbabdi (2018), for example, used structural MRI to quantify local scalp curvature.

Then, these statistics on curvature are compared against lifestyle measures acquired from the same group of people, making an attempt to match a subset of lifestyle measures to phrenological ideas of brain organization.

The scientists found that there was no correlation between phrenological claims and the actual structure of the skull.

Implications of Gall’s phrenology on modern neuroscience

Gall localized psychological and sensory functions to the cerebral context, which had consequences for his overall view of the nervous system. He believed that the cortex was the “highest” part of the brain system, not present in “low animals” like worms that only have a spinal cord.

Another important implication of Gall’s localization theory was an understanding of the difference between white and gray matter. Gall believed that if someone’s mental faculties are located in the gray matter on the brain’s surface, then the white matter must serve to interconnect regions associated with particular brain functions to the cortex and lower centers.

As in modern neuroscience, Gall believed the white matter was a collection of connection fibers.

References

Anderson, M. L. (2014). After phrenology (Vol. 547). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Flourens, P. (1846). Phrenology examined. Hogan & Thompson.

Gall, F. J. (1818). Anatomie et physiologie du système nerveux en général, et du cerveau en particulier (Vol. 3). Librairie Grecque-Latine-Allemande.

Greenblatt, S. H. (1995). Phrenology in the science and culture of the 19th century. Neurosurgery, 37(4), 790-805.

Lombroso, C. (2005). The criminal atlas of Lombroso. Editorial Maxtor.

Lucie, P. (2007). The sinner and the phrenologist: Davey Haggart meets George Combe. Journal of Scottish Historical Studies, 27(2), 125-149.

Morin, R. (2014). Phrenology and crime. The encyclopedia of theoretical criminology, 1-4.

Rawlings III, C. E., & Rossitch Jr, E. (1994). Franz Josef Gall and his contribution to neuroanatomy with emphasis on the brain stem. Surgical neurology, 42(3), 272-275.

Simpson, D. (2005). Phrenology and the neurosciences: contributions of FJ Gall and JG Spurzhei m. ANZ journal of surgery, 75(6), 475-482.

Spurzheim, J. G. (1826). The anatomy of the brain: with a general view of the nervous system. S. Highley.

Spurzheim G. Appendix to the Anatomy of the Brain Containing

a Paper Read Before the Royal Society on the 14th of May, 1829,

and Some Remarks on Mr. Charles Bell’s Animadvers.

Temkin, O. (1947). Gall and the phrenological movement. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 21(3), 275-321.

Young, R. M. (1968). The functions of the brain: Gall to Ferrier (1808-1886). Isis, 59(3), 250-268.