Procrastination, defined as the voluntary yet irrational delay of intended tasks and actions despite awareness of likely negative outcomes, is arguably the most common complaint among adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Research suggests that up to 95% of adults with ADHD chronically struggle with completing tasks and responsibilities in a timely way, which significantly impairs occupational, academic, financial, and interpersonal functioning.

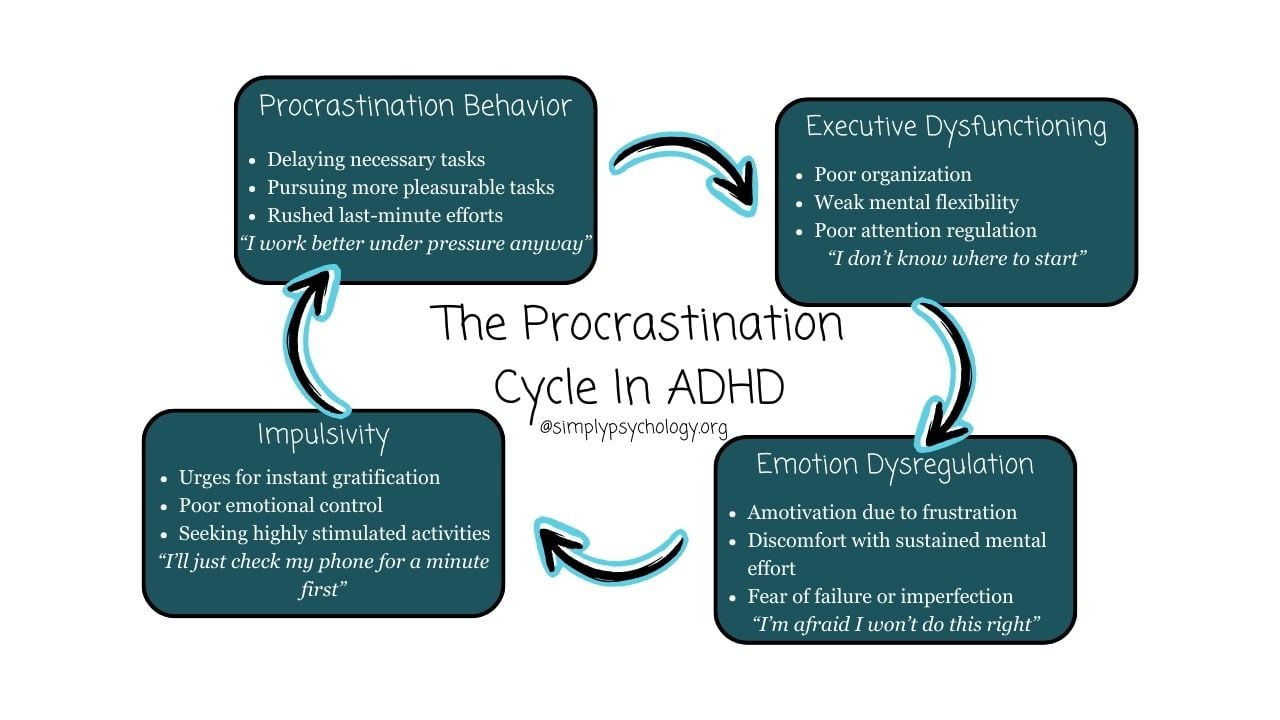

The high prevalence of procrastination among the ADHD population likely stems from the underlying neurological deficits in executive functioning skills such as organization, prioritization, working memory, and impulse control.

These areas of cognitive dysfunction, combined with problems regulating negative emotions, make it extremely difficult for adults with ADHD to get started, stay focused, and push through to complete tasks that seem boring, challenging, or anxiety-provoking.

Instead, those with ADHD tend to continually delay responsible duties in favor of pursuing more instantly pleasurable activities – often resulting in last-minute rushed efforts to meet deadlines or forgetting responsibilities altogether.

This article explores various reasons for procrastination in adult ADHD as well as science-based strategies to improve productivity and functioning.

What is Procrastivity?

Procrastivity refers to the common phenomenon where an individual makes plans to engage in high-priority responsibilities needed to reach a goal but instead engages in less urgent activities when faced with following through.

For example:

Imran intended to wake up early on Saturday morning to work on his taxes ahead of the looming deadline. However, once Saturday morning arrives, he snoozes his alarm, then suddenly changes plans and decides to reorganize his closet and go grocery shopping instead.

These procrastivity tasks, although useful, divert time and mental resources away from more pressing tasks, also known as “self-defeating productivity.”

Adults with ADHD frequently fall into traps of procrastivity when they hit mental barriers with primary tasks. By examining what makes procrastivity endeavors feel more readily achievable despite being lower priorities, strategies can be generated to help pivot focus back to main tasks.

Facets That Make Procrastivity Appealing

There are several elements that seem to make putting off high-priority tasks for procrastivity tasks appealing:

Familiarity – Procrastivity tasks often involve well-practiced routines around manual, clerical activities like household chores rather than new learning. Higher priority tasks usually require more cognitively demanding mental focus. Familiarity signifies competence.

Clarity – Procrastivity tasks appear simpler with clearer cause-and-effect chains. There is less uncertainty about the time, effort, and process required to complete procrastivity tasks compared to more complex priorities.

Actionability – Because procrastivity tasks tend to involve repetitive physical actions, there is a clear sense of being able to take the next step that spurs engagement. Less familiar primary tasks often lack obvious starting points.

Progress – Incremental progress tends to be easier to visually track with procrastivity tasks, creating a sense of momentum. Primary tasks often involve delayed results after sustained effort.

Endpoints – Procrastivity tasks usually have a defined stopping point, allowing a sense of accomplishment and closure within a foreseeable timeline. Necessary priorities seem endless.

These facets make putting less important things first feel more within reach. Using these features as a blueprint when tackling necessary tasks can help pivot behavior.

ADHD and Chronic Procrastination

There are multiple overlapping ADHD difficulties that set the stage for chronic struggles with procrastination. The most commonly cited reasons include:

Executive Dysfunction

- Poor organization make it hard to order steps needed to begin complex, multi-layered tasks

- Impaired working memory makes it hard to hold on to and sequence steps to follow through after starting

- Weak mental flexibility frequently derails forward momentum when inevitable obstacles arise

- Poor regulation of attention makes it hard to screen out digital and environmental disturbances.

Emotional Dysregulation

- Amotivation and hesitation to engage in tedious tasks due to learned feelings of frustration, anxiety, and uncertainty about one’s abilities

- Discomfort with mental strain and sustained expenditure of effort leads to prematurely abandoning duties

- Fears of failure or imperfection due to past difficulties establish an avoidance pattern with similar tasks

Impulsiveness

- Acting on urges for instant gratification leads to frequent derailment of work routines to pursue more pleasurable escapes

- Difficulties with regulating emotions or modulating arousal levels often facilitates rash re-directions

These ADHD deficits typically do not resolve fully with age; in fact, research indicates executive functioning impairments actually expand through the transition into adulthood.

Young adults report dramatic struggles when adolescents’ external supports around time and priorities fall away in college or independent living.

Impact on Functioning

When left unaddressed, chronic procrastination can snowball, creating cumulative problems across major domains of functioning. Common problematic outcomes include:

- Work/Career: Lateness, missed deadlines, unfinished projects, and perceivable laziness hamper job stability, promotion prospects, employability, and financial stability when individuals get fired or quit roles.

- Academics: Incomplete assignments and lack of study routines frequently cause failing grades, suspended financial aid, academic probation, and increased student loan burdens if forced to repeat failed courses. Dropping out may occur.

- Finances: Fines and fees accumulate from late credit card/loan payments, missed income tax deadlines or unfiled paperwork around insurance claims or other administrative duties. Quickly spiraling debt is common.

- Relationships: Friends and family members perceive the person as unreliable due to forgotten obligations, broken promises, missed events, or backing out of plans at the last minute due to incomplete tasks. Resentment and distrust build in relationships.

- Mental Health: Repeated failure experiences generate intense feelings of depression, anxiety, shame, self-loathing, low confidence, and despair. Preoccupation about incompetence dominates inner dialogue.

- Physical Health: Physical self-care routines like doctor appointments, taking medication consistently, exercise routines, and healthy eating fall by the wayside when mental resources focus solely on urgent matters. Sleep suffers without routines.

In summation, chronic procrastination for those with ADHD has deleterious downstream effects that cascade across nearly all major life areas, severely reducing overall wellness and quality of life.

Methods to Overcome ADHD Procrastination

Establishing structure around how time and priorities are managed is essential to mitigate chronic procrastination. However, due to the neurological basis of executive functioning deficits in ADHD, purely behavioral interventions are rarely sustainable.

Combining cognitive and emotional regulation skills with external compensations typically has the best outcomes.

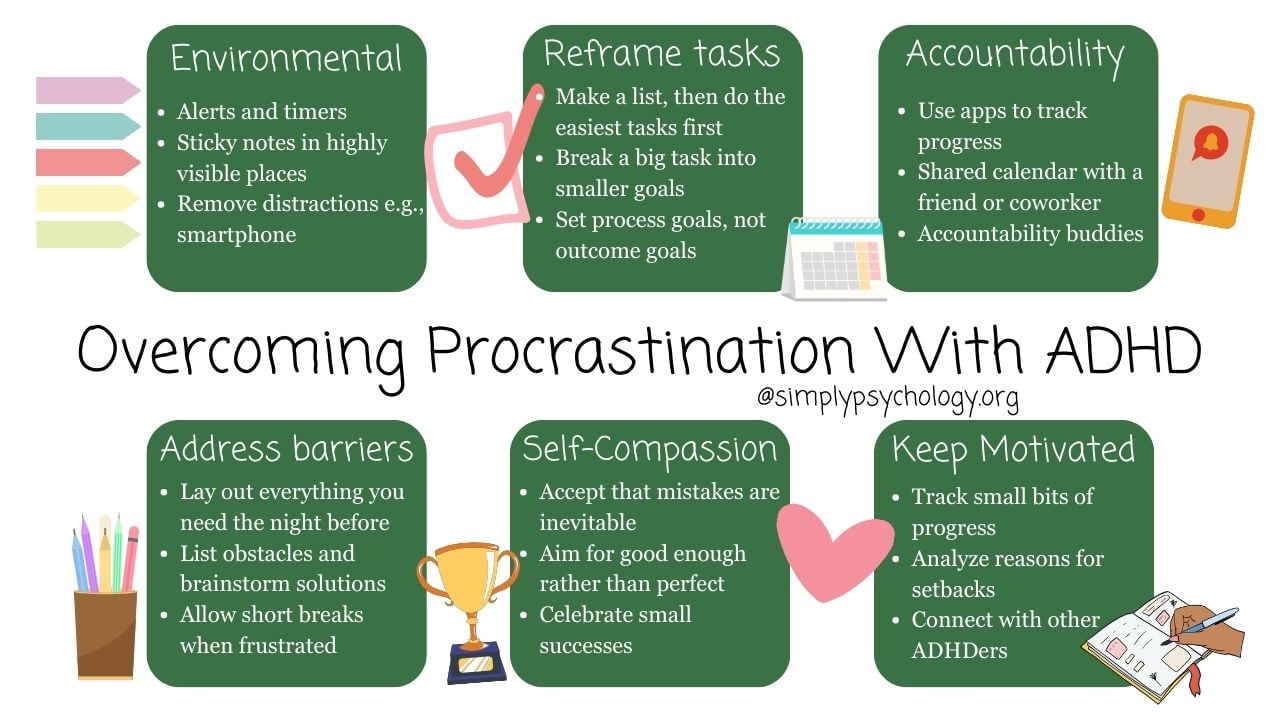

Environmental Supports

Because adults with ADHD often have limited introspective awareness around time passing and how on or off task they are, external sound, visual, and tactile cues are vital prompts to pivot focus. Options include:

- Smartphone alarms/alerts for scheduling start times, reminders of next steps, intervals for brief stretch breaks, notifications to transition between tasks and log-off times

- Visual timers showing elapsed time dedicated to a task helps gauge progress and recalibrate lagging energy. Useful for work blocks and breaks.

- White noise/music playlists helps narrow external distractions during focus times

- Wall calendars/planners, white boards, post its marked with dated to-do lists etc. all make responsibilities tangible and cued

If you work at a desk, you could put post-it notes of tasks you need to do around your monitor screen. This way, they are always in your line of sight, and you can physically remove the post-it note once the task has been completed.

Light Physical Anchors

Simple physical sensations can serve as useful anchors indicating needing to initiate a new task or shift back to work mode. For example:

- Moving to a different chair or location dedicated for work/study routines

- Putting on noise cancelling headphones or other wearable item worn just for work mode

- Sipping from a distinctive mug, water bottle or snacking from a dedicated plate reserved just for getting tasks done

Accountability Partners

Connecting with others helps to galvanize follow-through on difficult tasks. Useful approaches involve:

- Study groups to maintain motivation for academic routines

- Body doubling – have friends or even paid professionals work alongside, in person or virtually for complex projects

- Working from communal office spaces or libraries heightens social pressures to avoid non-work related internet temptations

- Sharing work calendars allows others to check on dynamic progress and provide encouragement

Managing Cognitive and Emotional Barriers

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy techniques could equip individuals with ways to dismantle mental roadblocks both before and as they arise:

Prepare for Common Rationalizations

- Predict typical self-talk patterns that enable procrastination: “I work best under pressure” or “The task is too boring.”

Address Perfectionism

- Counter notions that conditions must be “perfectly comfortable” to start through cost/benefit analyses of delays

Reframe Tasks as Accomplishable

- Break overwhelming duties down into subtasks framed as experiments lasting concentrated bits of time – “I will work solely on this report for just 20 minutes.”

Set Process Goals Over Outcome Goals

- Define highly specific next steps rather than preoccupying with a final product. Track small units of engagement. For example, instead of saying, “I want to finish my project,” reframe this to say, “I will aim to complete 1 hour of research for my project today.”

Allow Flexibility with Task Routines

- Permit shifting between subtask items to harness bursts of motivation across lower priority items when energy lulls. For example, make a list of tasks you want to do, then complete the easiest ones first to get the ball of motivation rolling.

Anticipate Emotional Triggers

- Note bodily cues, self-talk patterns, and situations that spur frustration, uncertainty, and the urge to escape difficult aspects of priority tasks.

Apply Emotion Regulation Tactics

- When negative sensations arise, use tactical breathing, mindfulness practices, taking structured pauses to self-soothe before continuing OR strategic avoidance by switching to lower stakes aspects of responsibilities.

Self-Compassion Over Self-Criticism

When setbacks occur, frame lapses matter-of-factly as information gaining about personal productively patterns rather than evidence of personal inadequacy. Analyze context clues about barriers that arose and problem-solve adjustments. Each brief re-start back to duties after distraction builds self-regulatory strength.

ADHD coach Caren Magill encourages us to reflect on why exactly we want to complete certain tasks:

“Forcing yourself to do things is something we all have to do in life to some degree, but there’s a lot of things we force ourselves to do that are unnecessary or that we just think other people want us to do or that we think we should do to be a good person and it’s really good to question those things.”

“How badly do you really want this thing?… If you were to just put it down and walk away, how would that make you feel inside? Does that give you a little sense of freedom, or does it give you a sense of self-betrayal?”

Caren Magill, ADHD Coach

Cultivating Positive Motivation and Self-Efficacy

Beyond concrete organizational supports and tactics for managing cognitive/emotional barriers associated with tasks, adults with ADHD also struggle with overarching fatigue, shame, and diminished self-concepts related to chronic difficulties that erode motivation over time.

Intentionally fostering more helpful mindsets, accountability and seeking evidence countering deterministic thinking is imperative.

1. Set Activity Level Goals Not Outcome Goals

Rather than preoccupation over tangible deliverables completed, centralize tracking simple behaviors indicating task engagement. Tiny bits of visible progress powerfully chip away at lost motivation from former failed efforts.

Example: Instead of a goal to "finish my 10-page paper," set a goal to "write for 30 minutes tonight"

2. Collect Accountability Data

Self-tracking execution of incremental subtask steps provides concrete counters to emotionally charged global perceptions of being unable to accomplish goals. Even basic notes about partial efforts refute notions like “I can never follow through” which overwhelm motivation.

Reframe setbacks as practice rather than proof of inherent deficits. Model self-talk highlighting that missteps are inevitable for all humans rather than evidence of irredeemable personal flaws.

Think about whether you would tell your best friend there was something inherently wrong with them if they forgot something. Hopefully, you wouldn’t – so try to afford yourself the same kindness.

Example: Note in a bullet journal spending 15 minutes reviewing sources before writing, checking off incremental progress

3. Reconnect With Core Values

Regularly revisiting the links between unpleasant duties and underlying guiding principles valued internally re-energizes lagging efforts, especially during tedious segments of complex goals. Using external visual quotes, images, and other tactile associations helps sustain meaning-making.

Example: Display an inspirational quote on value of education near desk as a reminder of why completing a degree matters

4. Ongoing Skill Development and Relapse Prevention

Executive functioning deficits and problems with automaticity of useful habits both contribute to the chronic waxing/waning cycle of follow-through struggles for adults with ADHD despite genuine desires and efforts to change behavior.

Practicing radical self-acceptance around the two-step forward, one-step-backward nature of neurological dysregulation allows more emotional resilience. Skillfully analyzing periodic backslides for improvement opportunities fosters agency over helpless resignation.

Example: "I got distracted after 10 minutes of writing, but that's 10 more minutes than if I hadn't tried at all"

5. Expect Setbacks But Stay the Course

Adopting a neutral stance that periodic failures and blocks in organizational systems and self-regulation practices used for coping are annoying but inevitable gremlins aids perseverance after a maladaptive procrastination relapse rather than full abandonment of the approach.

Mini self-compassion pep talks before getting back re-centered reduce shame. Using a micropause to select the smallest, easiest aspect among overwhelming demands to re-enter the workflow cycle is the central ADHD relapse prevention pivot point.

Example: When late for work again, say to self "ADHD makes this hard but I will keep trying strategies to get out the door earlier"

6. Refine But Don’t Reinvent After Stumbles

Rather than perceiving periodic failures to execute useful strategies as indications that whole interventions are fundamentally flawed, probe to determine unique breakdown vulnerabilities needing enhancement.

Common examples include inadequate cuing, unrealistic time allotments for total workload volume before exhaustion, ineffective spaces conducive for style of task etc.

Exploring better ways to bolster existing frameworks smooths sustainability.

Example: Buying multiple phone chargers after missing alarm when phone died to avoid overreacting and abandoning alarm use altogether

7. Probing for Patterns Actively Curbs Relapse Triggers

Intentionally tracking specifics around unwanted procrastination slip-ups unveils trends about contexts where struggles concentrate as well as types of blocks most routinely occurring.

Keeping dated written accounts of delayed goals, and diversionary activities that hijack focus along with associated thoughts, feelings, and situational factors fuels both clinical analyses as well as self-advocacy conversations needed for securing improved workplace/academic accommodations and relational supports.

Demonstrating self-awareness around ADHD barriers communicates neurodiversity differences rather than indifference.

Example: Journaling about when and why sidetracked from tasks unveils tendency to struggle after lunch break needs a revised routine

8. Meaningfully Connecting With Community

Purposefully sharing learned insights from successful experiments, failure investigations, and advocacy needs with other neurodivergent networks combats isolation and normalizes common frustrations.

Relatability fosters accountability partnerships. Countering stereotypical societal shaming with inspiring stories of those creatively thriving through similar executive functioning challenges uplifts and teaches methods for translating ambitions into actions.

Example: Joining ADHD Facebook groups to share ideas about task gamification that improved video game design work momentum

Conclusion

In summary:

- Chronic procrastination in ADHD stems from executive functioning deficits and emotional regulation barriers interfering with motivation and follow-through.

- Creating structured external support systems is vital – environmental cues, prompts, timers etc. – to compensate for neurological barriers.

- Build skills for framing tasks in doable chunks tracked via process goals rather than preoccupation with final outcomes. Use emotional regulation tactics to manage discomfort or uncertainty.

- Frequently analyze periods of backsliding neutrally as information gaining about unique personal patterns. Refine approaches based on lessons learned about specific vulnerabilities.

- Radically accept the inevitability of periodic setbacks given the ADHD challenges with automaticity around habits. Stress growth mindset building through resilience.

- Share stories about failures and successes openly with ADHD communities to combat isolation and build useful partnerships. Model creative adaptation.

The high incidence of such functional impairments warrants self-compassion. Mapping predictable barriers fosters agency in channeling ambitions into actionable steps despite neurological roadblocks.

References

Altgassen, M., Scheres, A., & Edel, M. A. (2019). Prospective memory (partially) mediates the link between ADHD symptoms and procrastination. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 11, 59-71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-018-0273-x

Oguchi, M., Takahashi, T., Nitta, Y., & Kumano, H. (2021). The moderating effect of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms on the relationship between procrastination and internalizing symptoms in the general adult population. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 708579. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.708579

Ramsay, J. R. (2017). The relevance of cognitive distortions in the psychosocial treatment of adult ADHD. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 48(1), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000101

Ramsay, J. R. (2020). Cognitive interventions in action: Common issues in cognitive behavior therapy for adult ADHD. In J. R. Ramsay, Rethinking adult ADHD: Helping clients turn intentions into actions (pp. 87–123). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000158-006